The future of infrastructure.

What does the infrastructure of tomorrow look like?

The future of infrastructure (UK)

The times they are a-changin’.

Infrastructure is the stuff civilization is made of. If culture is the software, infrastructure is the hardware, consisting of things like roads, bridges, and sewers. This did not change much between the Roman Empire and the industrial revolution. Rail, automobiles, mass production, power grids, telecommunications, global shipping, and aviation dramatically expanded the definition of infrastructure as governments and corporations raced to service the needs of an increasingly productive, complex, and interconnected world.

We are now in the middle of another transformational moment, with formidable challenges and innovative technologies converging to create an unprecedented opportunity to build the infrastructure of tomorrow. The current infrastructure boom is characterized by unprecedented scope. According to fund managers and institutional investors who actively invest in infrastructure, the asset class arguably includes everything from satellites and electric vehicle charging networks to schools and senior living facilities (Figure 1). There is no universal agreement, but it is hard to deny that modern civilizations have more complex needs, and the interconnectedness of modern life means investments in the systems that support it are better considered holistically.

Figure 1. When it comes to investing, what do you consider to be infrastructure?

To discern what’s behind the newfound enthusiasm for this often-overlooked asset class—and why it is viewed differently than the past—we collaborated with ANZU Research and Global Fund Media to survey 84 managers (general partners, or GPs) and institutional investors (limited partners, or LPs). Through the results of that survey and additional accompanying interviews of participants, we identified five factors driving today’s conversations around infrastructure investing:

- Climate change

- Demographic shifts

- Deferred maintenance

- Technological innovation

- Geopolitics

Climate change.

The issue of climate change is a key driver of this more expansive approach. Forward-thinking investors are focusing squarely on the opportunities revealing themselves from this crisis. Succinctly summarizing the investment thesis for any number of infrastructure projects, Vincent Gerritsen, Head of UK and Europe for Morrison & Co, says, “Climate change is an established threat to humanity.”

Infrastructure, in other words, can no longer be considered as something built exclusively for its own benefit, running roughshod over ecosystems that happen to be in the way. Environmentalists and conservationists were fringe figures not long ago, but with sustainability having entered mainstream conversations over the past decade, infrastructure investments are increasingly being evaluated for their potential impact on the surrounding environment.

This is no abstract concept. According to Hamish Mackenzie, Head of Infrastructure at DWS, "Decarbonization policies and technological change are reshaping the global economy, and the infrastructure investment gap has increased substantially as a result, with multi-trillion-dollar infrastructure policy measures across the U.S. and Europe focusing on achieving net zero and aimed at supporting the post-pandemic recovery."

Demographic shifts.

We will have to adapt our infrastructure in other ways as well. Low birth rates and aging populations pose a relatively new challenge in many developed countries as the ratio of dependents to productive society members rises. Elder care will move from residential communities to permeate every facet of life in many richer nations. Many poorer countries continue to see booming growth, resulting in unprecedented population density in megalopolises. Remote work has fundamentally altered concepts of home and work, changing how people move about. Transportation and energy use are closely tied to all these trends, meaning global infrastructure must be adapted if we are to avoid the trap of building for yesterday rather than tomorrow

Deferred maintenance.

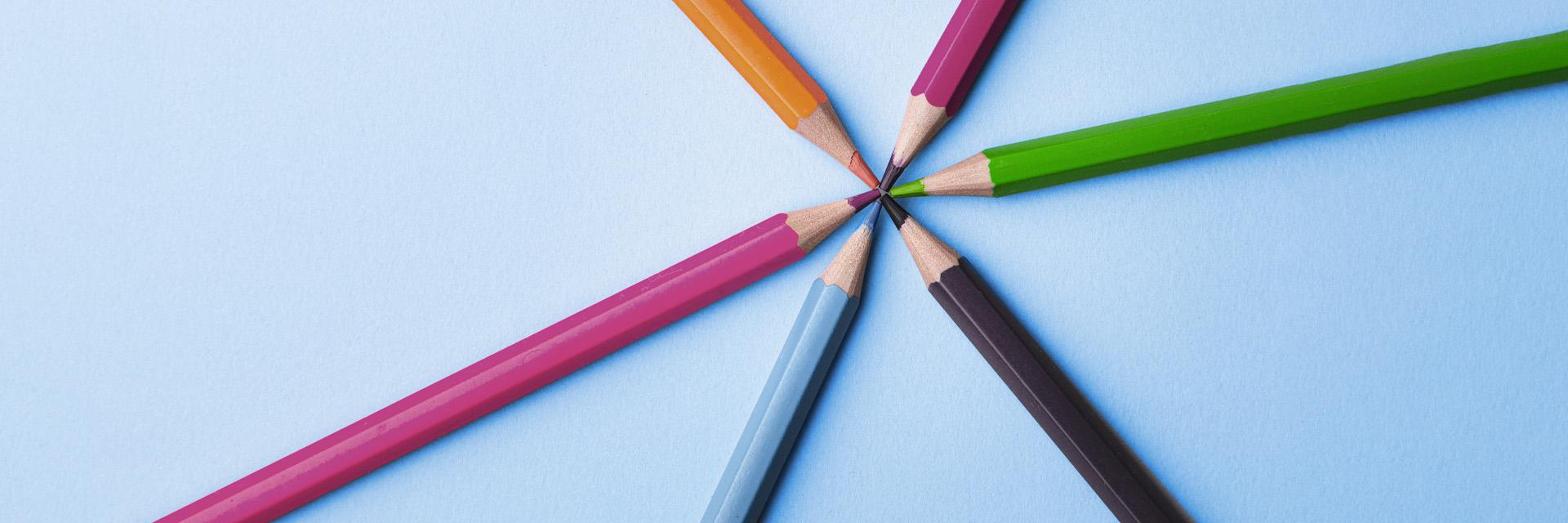

Another simmering problem galvanizing the current infrastructure boom is deferred maintenance. Many countries on the leading edge of the industrial and communications revolutions saw early infrastructure investments pay off in spectacular ways. But those same assets were often neglected in the years that followed, as budget resources flowed elsewhere. The United States is a vivid example of this phenomenon. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), almost two out of three types of infrastructure deserve a grade of D+ or lower (Figure 2). Even this dire appraisal may understate the problem. The country’s rail system, which merited the highest grade, falls far short of standards found in many other countries. Awarded a middling grade of B-, ports were clearly overwhelmed as trade resumed in the wake of the pandemic. US ports handled almost 25 million inbound 20-foot units in 2021. This represents four times the volume of 1995, despite reliance on the same infrastructure. The system is reaching its limits, and further growth cannot be accommodated by incremental improvements.1

Figure 2. ASCE infrastructure categories and grades

Innovation.

Faced with such formidable challenges, infrastructure investors can take heart from the fact that we have never been better equipped to tackle them from a technological standpoint. With venture capital funding a constant stream of innovative ideas in technology centers around the world, computing power growing apace, and the flow of data prompting further discoveries and ideas, infrastructure innovation is at an all-time high.

Data is a key focal area for infrastructure investors who recognize its critical role. We are used to thinking about telecommunications infrastructure facilitating the transmission of knowledge, but we are entering a profoundly different age where everyone, from farmers in Rwanda to bus drivers in Malaysia, will interact with and learn from data on the job. Furthermore, autonomous monitoring systems will not only gather data on infrastructure projects but will optimize systems in real time. Justin De Angelis, Partner at Denham Sustainable Infrastructure, notes that “If COVID taught us anything, it’s that digitization and data are king. Data centers are a significant infrastructure investment, and energy efficiency and sustainability around them should be a significant focal area.”

Applying new technology to infrastructure is not easy. Given the cost and longevity of these projects, it is naturally tempting to stay with proven technologies. Conservative approaches are adopted to minimize risk, but they face the risk of irrelevance in times of rapid change. Selecting the best new technology may be even more fraught, especially when track records of success are short. Partnering with seemingly clear frontrunners is no guarantee of success, as anyone who remembers the Betamax videotape format can attest.

Geopolitics.

War has driven technological advancements through the ages, but usually in the pursuit of military advantage. Occasionally, other vulnerabilities are laid bare, spurring action. The Russian invasion of Ukraine precipitated a humanitarian crisis and countless stories of heartbreak. As it drags on, it also threatens to cast a shadow over the lives of millions more as energy supplies to Europe are imperiled. Yet there may be a silver lining. As tragic as it is, The World Economic Forum listed infrastructure as one of its twelve pillars of global competitiveness. as it is, Justin De Angelis, Partner at Denham Sustainable Infrastructure says, “The Ukraine situation is – in an odd kind of way – good for the energy transition overall.” Reto Schwager of Patrimonium agrees, stating that “The Ukraine and Russia conflict will certainly have a tremendous positive effect on the alternatives to the conventional energy businesses.”

Where to next?

Change, uncertainty, and existential threats make compelling arguments for infrastructure investment, but opportunities for growth may be even more persuasive. According to the World Bank, infrastructure quality is highly correlated to GDP growth per capita. The U.S. Congressional Budget Office estimates that “every dollar spent on infrastructure brought an economic benefit of up to $2.20.” The U.S. Council of Economic Advisers has calculated that $1 billion of transportation-infrastructure investment supports 13,000 jobs for a year.”2 Additionally, the World Economic Forum (WEF) listed infrastructure as one of its twelve pillars of global competitiveness, where it is grouped with institutions, the macroeconomic environment, and health and primary education as necessities.

The World Economic Forum listed infrastructure as one of its twelve pillars of global competitiveness.

Furthermore, infrastructure’s role as an economic accelerator is buffered by its ability to hedge against inflation. Despite vulnerability to labor shortages and rising materials costs, inflation-linked cash flows make infrastructure assets an attractive proposition.

Preqin points to investor worries over inflation as a key motivator, noting that “the inflation protection afforded by many infrastructure assets is often cited among the top reasons investors allocate to the asset class.”3 Infrastructure, it seems, has something for everyone. As Vincent Gerritsen of Morrison & Co says, “Infrastructure is an essential component of nation-building and inclusion, delivering long-term value for investors, the environment and society.

Meanwhile...

The United States and other countries that industrialized early are faced with the task of maintaining, improving, or mothballing obsolete infrastructure. Developing nations, on the other hand, can find themselves in a position to play leapfrog. Lacking the ability to finance large infrastructure projects internally, many are signing up to play a role in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), widely viewed as the world’s most ambitious infrastructure endeavor currently underway. Setting aside any debate over human rights, environmental degradation, or ulterior geopolitical motives, there is no doubt that BRI is having a transformative effect on areas that were previously neglected. A centerpiece of Xi Jinping’s foreign policy, this massive undertaking was launched by the Chinese government in 2013 as a modern echo of the ancient Silk Road trade routes, investing in nearly 150 countries and international organizations across the Eastern Hemisphere.

Debt traps have long been a problem for low- and middle-income nations short on financing for critical infrastructure. Depending on one’s perspective, China’s role as a willing lender can be characterized as anything from benevolent to predatory.

What does this look like on the ground? Ethiopia provides a striking example. With 110 million people, it is the largest country in East Africa, next door to Djibouti. Yet it traditionally took seven days overland from Addis Ababa to reach Djibouti’s port at the mouth of the Red Sea on one of the world’s busiest shipping routes. With Chinese funding, expertise, and labor, Africa’s first electrified railway opened in 2018 and shrank travel time to ten hours, opening the African interior as a market and source of raw materials.4

As impressive as BRI is, it may ultimately demonstrate the pitfalls as well as the benefits of central planning. China is lauded for its ability to deliver large-scale projects such as the Three Gorges Dam and the world’s largest high-speed rail (HSR) network, but without the checks and balances found in freer markets, financial viability sometimes seems to be an afterthought. With over 40,000 kilometers of track, for example, the scale of China’s HSR network is matched only by the size of its debt financing: $900 billion USD and counting.5 Conceived as a cohesive vision, BRI is nevertheless subject to countless risks across multiple jurisdictions and markets.

Partner nations are also at risk. Debt traps have long been a problem for low- and middle-income nations short on financing for critical infrastructure and economists have speculated that China’s lending practices have contributed to their debt crises. Depending on one’s perspective, China’s role as a willing lender can be characterized as anything from benevolent to predatory.6 Some nations are likely to thrive, thanks to closer integration in the global economy. Others such as Sri Lanka, already teetering on an economic precipice, risk financial ruin and the potential loss of control over strategic assets.

China is hardly the only nation forging ahead with groundbreaking infrastructure projects. Flush with oil money, Saudi Arabia is proposing to reinvent life for millions of people expected to live and work in The Line (aka Neom), a radically reimagining of city life which forms a cornerstone of the country’s broader Vision 2030 plan to diversify and transform itself. A technologically advanced 200-meter-wide project extending 170 kilometers to the country’s Red Sea coast and rising 500 meters above sea level, The Line is being built for nine million inhabitants.7 Despite the undeniable appeal of a clean and efficient metropolis relying only on renewable energy, it remains to be seen if a population density 30 times greater than Singapore’s in an area of 13 square miles (34 sq. km) is attractive to enough people, particularly when a main selling point is pervasive data harvesting from its inhabitants. Transformative projects like this may prove to be the ultimate manifestation of the risks inherent in a “build it and they will come” approach.

Endnotes

1 Editorial staff, Time For Major Investments In New Container Ports And Terminals, gCaptain, August 27, 2022.

2 Jared Katseff, Shannon Peloquin, Michael Rooney, and Todd Wintner, Reimagining infrastructure in the United States: How to build better, McKinsey & Company, June 6, 2020.

3 Preqin, September 2022, www.preqin.com.

4 Henry Wismayer and Marcus Westberg, A Remarkable Rail Journey Into the Horn of Africa’s Past, and Future, The New York Times, April 8, 2019.

5 Ashish Dangwal, A Whopping $900B Debt—China’s OnceProfitable High-Speed Railways Now Heading Towards A Trillion Dollar Disaster, the EurAsian Times, July 7, 2022.

6 Nilanthi Samaranayake, Chinese Belt and Road Investment Isn’t All Bad—or Good, FP, March 2, 2021.

7 Neom, September 2022, www.neom.com.

What is next?

Continue reading the full paper to discover the preferences and concerns evolving infrastructure alongside a changing world.

More insights for asset managers.

Information provided by SEI Investments Distribution Co.; SEI Institutional Transfer Agent, Inc; SEI Private Trust Company, a federally chartered limited purpose savings association; SEI Trust Company; SEI Investments Global Fund Services; SEI Global Services, Inc.; SEI Investments–Global Fund Services Limited; SEI Investments–Depositary and Custodial Services (Ireland) Limited; SEI Investments–Luxembourg S.A.; and SEI Investments Global (Cayman) Limited, which are wholly owned subsidiaries of SEI Investments Company. The Investment Manager Services division is an internal business unit of SEI Investments Company. This information is provided for education purposes only and is not intended to provide legal or investment advice. SEI does not claim responsibility for the accuracy or reliability of the data provided. Information provided by SEI Global Services, Inc.